The U.S. Open will be contested at The Olympic Club in San Francisco June 14-17. The USGA is highlighting the champions produced by this golf-rich area. The first of two parts focuses on male golfers. Part II discusses great female players.

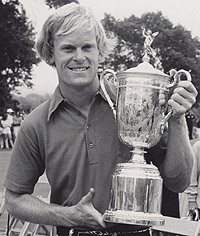

Safe to say, Johnny Miller counts as the most accomplished male golfer from the San Francisco Bay Area. He not only won 25 times on the PGA Tour, he offered a signature memory during his 1973 U.S. Open triumph – bringing mighty Oakmont Country Club outside of Pittsburgh to its knees in a transcendent, final-round 63.

Ken Venturi, like Miller, grew up in San Francisco (they both attended Lincoln High in the city’s Sunset District). Venturi collected 14 tour victories, including his own memorable U.S Open win – when he survived 36 holes in smothering heat and humidity to prevail at Congressional Country Club in 1964.

| |

| Johnny Miller won the 1973 U.S. Open with a brilliant final-round 63 at Oakmont C.C. (USGA Museum) |

As the Open returns to The Olympic Club, tucked near the ocean in the southwest corner of San Francisco, it seems appropriate to reflect on the area’s rich golf tradition. Just as it’s probably unprecedented for one high school to produce two U.S. Open champions – plus another player, Bob Lunn, who won six PGA Tour events and once tied for third in the Open – few metropolitan areas can match the Bay Area’s depth of talent.

Start with its own Grand Slam: George Archer (also from San Francisco) won the 1969 Masters; Miller, Venturi and Lawson Little captured the U.S. Open, Miller and Tony Lema (Oakland) took the British Open and Bob Rosburg (San Francisco) won the 1959 PGA Championship. Little also won what was known as the Little Slam, claiming the U.S. and British amateur titles in 1934 and 1935.

Or consider this tidy triumvirate: In 1964, The Olympic Club alone boasted three USGA champions in Venturi (Open), Miller at age 17 (Junior Amateur) and William D. Higgins (Senior Amateur). Nice year.

And don’t forget about Nathaniel Crosby’s improbable victory in the 1981 U.S. Amateur. Crosby, son of singer/actor/golf lover Bing Crosby, won the Amateur right there on Olympic’s Lake Course, twice erasing big match-play deficits to become a USGA champion at age 19.

This storied tradition of standout players, in many ways, traces to the many acclaimed courses in the Bay Area. Venturi and Miller both grew up playing Harding Park, one of the finest public courses in the country and host of an annual PGA Tour event, the Lucky International, in the 1960s.

Sharp Park and Lincoln Park also were challenging, well-maintained municipal layouts back in the day, giving Venturi and the players of his era access to several challenging courses. It didn’t hurt that he and Miller were granted junior memberships at The Olympic Club during their teenage years; Venturi also played occasionally at nearby Lake Merced Golf Club (host of this year’s U.S. Girls’ Junior Championship) and caddied at San Francisco Golf Club.

“We had a lot of firemen, policemen and people like that who played golf,” says Venturi, now 81 and living outside Palm Springs, Calif. “They taught you. And the city was really good about it – they let you play Harding and they wouldn’t charge you. They helped out kids. It was a rare deal.

“On weekends, you couldn’t get tee times – so they’d send me and three other kids out to the second tee early in the morning. They’d say, ‘When you see guys on the first fairway, get going.’ ”

As for his early connections to Olympic, Venturi says, “It was a big deal to be able to play Olympic Club in those days – that was really an honor. They treated you well, as long as you were polite and handled yourself nicely. If you were courteous, you were accepted.”

It makes sense, on many levels, for the Bay Area to crank out all these USGA champions. Given the scarcity of land in a densely populated urban setting, most of the courses are tight, tree-lined and demanding, with small greens.

Venturi and those who followed him had little choice: They learned how to control their shots.

“We became pretty straight,” he says. “Now you can hit it in the trees at Olympic and get the next shot on the green – we’d pitch it out when we hit it in the trees, if we could find the ball.”

Nathaniel Crosby, not surprisingly, carved his own distinctive path into the game. His father hosted the annual tournament/party long known as the Bing Crosby National Pro-Am at Pebble Beach, giving young Nathaniel early and captivating exposure to golf.

Crosby handed out scorecards and pencils for the starter at Cypress Point, and he followed celebrities around Cypress, Pebble and Spyglass Hill during his dad’s tournament. Then, to cement his interest in the game, another Northern California kid – Miller – climbed to dizzying heights, not only winning the Open in ’73 but also rolling to eight PGA Tour victories (including the Crosby) the following year.

So the Bay Area’s success began to feed off itself.

| Great Bay Area Champions | |

| George Archer (1969 Masters) Ron Cerrudo (1966 World Amateur; 1967 Walker Cup Nathaniel Crosby (1981 U.S. Amateur; '83 Walker Cup Charles Ferrera (1931, 1933 Amateur Public Links) William D. Higgins (1964 USGA Senior Amateur) Johnny Miller (1964 U.S. Junior Am, 1973 U.S. Open) Tony Lema (1964 British Open) Lawson Little (1934-35 U.S. Amateur; 1940 U.S. Open; 1934 Walker Cup) Robert Lunn (1963 Amateur Public Links) Bob Rosburg (1959 PGA Championship) Kenneth Towns (1949 Amateur Public Links) Ken Venturi (1964 U.S. Open) Jim Wiechers (1962 U.S. Junior Amateur) |

Crosby, like Venturi, Miller and the others before him, often played in junior tournaments while growing up in the Bay Area. The Northern California Golf Association already was active and vibrant, and it helped create a junior-friendly environment for serious and ambitious young players.

When he reached college age, Crosby crossed the country to play at the University of Miami. There, he learned to appreciate another element in the Bay Area’s golf heritage – its mild climate.

Crosby could hit only about 30 shots on the range in South Florida before he felt like he was in a sauna. He came to miss the cool conditions back home – where the weather seldom limited practice, beyond wintertime rain – and he returned there every summer.

That included 1981, when Crosby etched his name in USGA lore by becoming the youngest player to win the Amateur (a record later broken by Tiger Woods). He had tasted morsels of success in national tournaments, such as reaching the quarterfinals of the North-South Amateur at Pinehurst No. 2 in North Carolina, but he hadn’t won an event of significance – and he was young and green.

This didn’t stop him from weaving a storybook tale, Bing’s kid spinning his magic by storming back to win in the semifinals and finals. He wore one of his dad’s old medals around his neck, rubbing it for good luck at vital moments. Bing Crosby had died less than four years earlier, while playing golf in Spain, and young Nathaniel channeled his old man’s showmanship.

“I’m not sure you could say divine intervention played a role,” Crosby says now. “But at the time I was winning it for my dad, for sure. That was foremost in my thinking. Sometimes, higher goals than serving yourself spur you to great things.”

Crosby might have been the most unlikely USGA champion with Bay Area newsContents, but Venturi overcame the most obstacles. He enjoyed an accomplished amateur career – famously dueling with Harvie Ward in the finals of the 1956 San Francisco City Championship, with 10,000 spectators tagging along at Harding Park – but Venturi’s path to prominence as a pro included several speed bumps.

He overcame a severe stutter, weathered two crushing Masters losses, sustained lingering injuries from a September 1961 car accident and disappeared into a long, maddening, career-threatening slump. So playing 36 holes in scorching heat and humidity, amid U.S. Open tension, seemed a fitting trial.

Venturi became an enduring symbol of perseverance in winning the Open under brutal conditions on June 20, 1964. He fought through dehydration and exhaustion, but it’s also important to remember where his career stood at the time. He hadn’t won in nearly four years and, less than a month earlier, he was practically broke and on the brink of returning to the Bay Area to find a real job.

Then, abruptly, Venturi’s career arc dramatically changed. Dr. John Everett, a Congressional member, walked the final 18 holes alongside him, providing water and salt tablets. Everett worried for Venturi’s life – and instead he helped to forever change his life.

“It’s hard to express, but to come back borders on a miracle,” Venturi says of his long-ago Open triumph. “It’s storybook. It’s fictional.”

Venturi forged a trail – from San Francisco upbringing to U.S. Open champion to prominent television analyst – eventually duplicated and improved upon by Miller. He put together one of the most dominant stretches in PGA Tour history, winning 12 tournaments in 1974 and ’75.

Not coincidentally, Miller’s two major championship wins – the U.S. Open in 1973 and British Open in ’76 – served as bookends to this flurry. He was known as one of the most precise iron players in the game’s history, which led to an unmistakable bravado.

“It was sort of golfing nirvana,” Miller once said. “I’d say my average iron shot for three months in 1975 was within five feet of my line, and I had the means for controlling distance. I could feel the shot so well.”

Or, as Venturi says, “Johnny had quite a record there for a while, especially on the West Coast. He was an aggressive player and a very courageous player. He’d take chances – and he had the game to do it.”

Ron Kroichick covers golf for the San Francisco Chronicle and has previously written for USGA websites.